From Nuclear Reactor to Acting Stage: The At-Sea Chapter

Join me as I recount my challenging and transformative years aboard a nuclear-powered warship, where daily drills, Pentagon inspections, and a pivotal lesson from my Commanding Officer unexpectedly shaped my approach to acting and life.

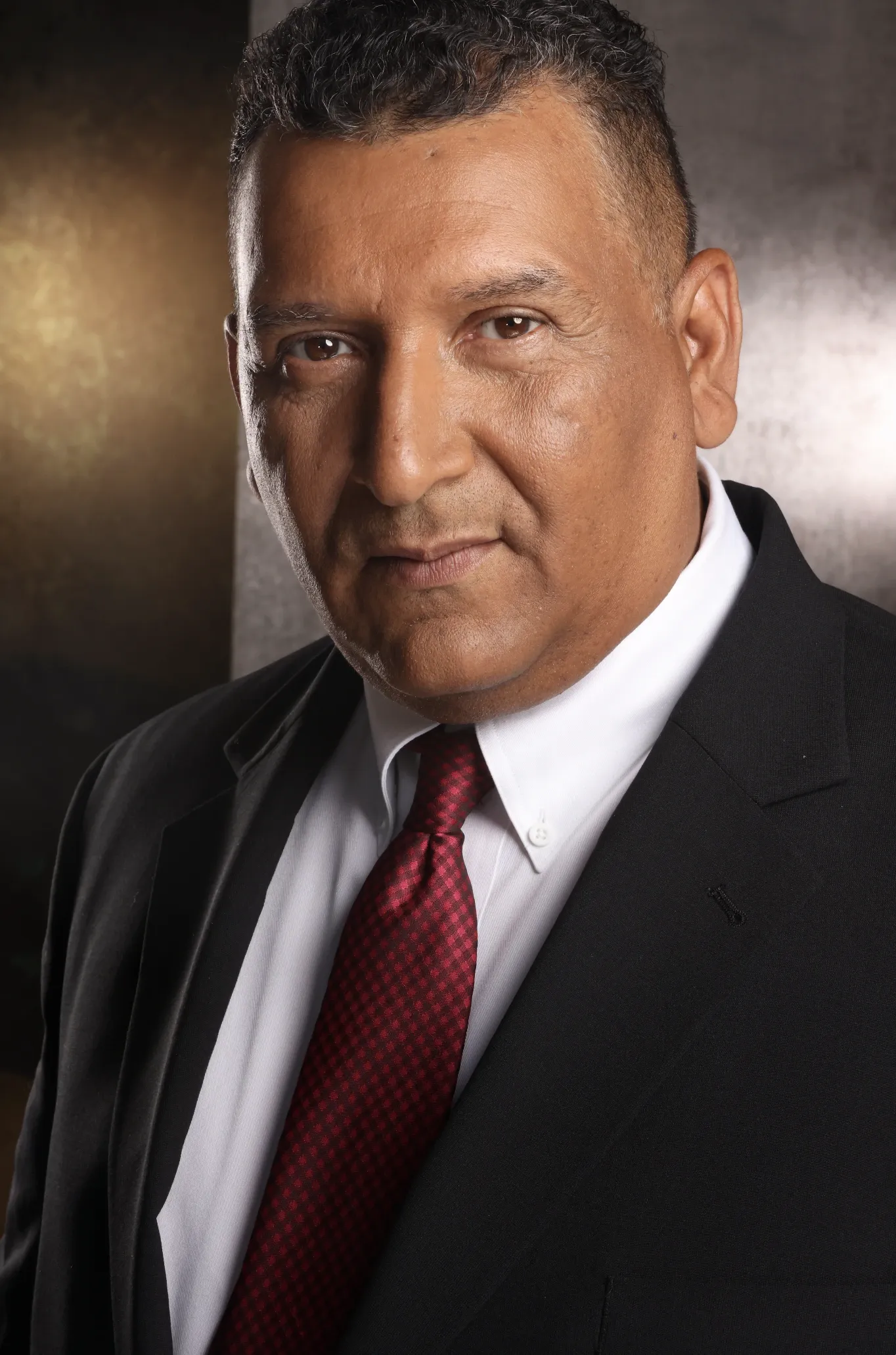

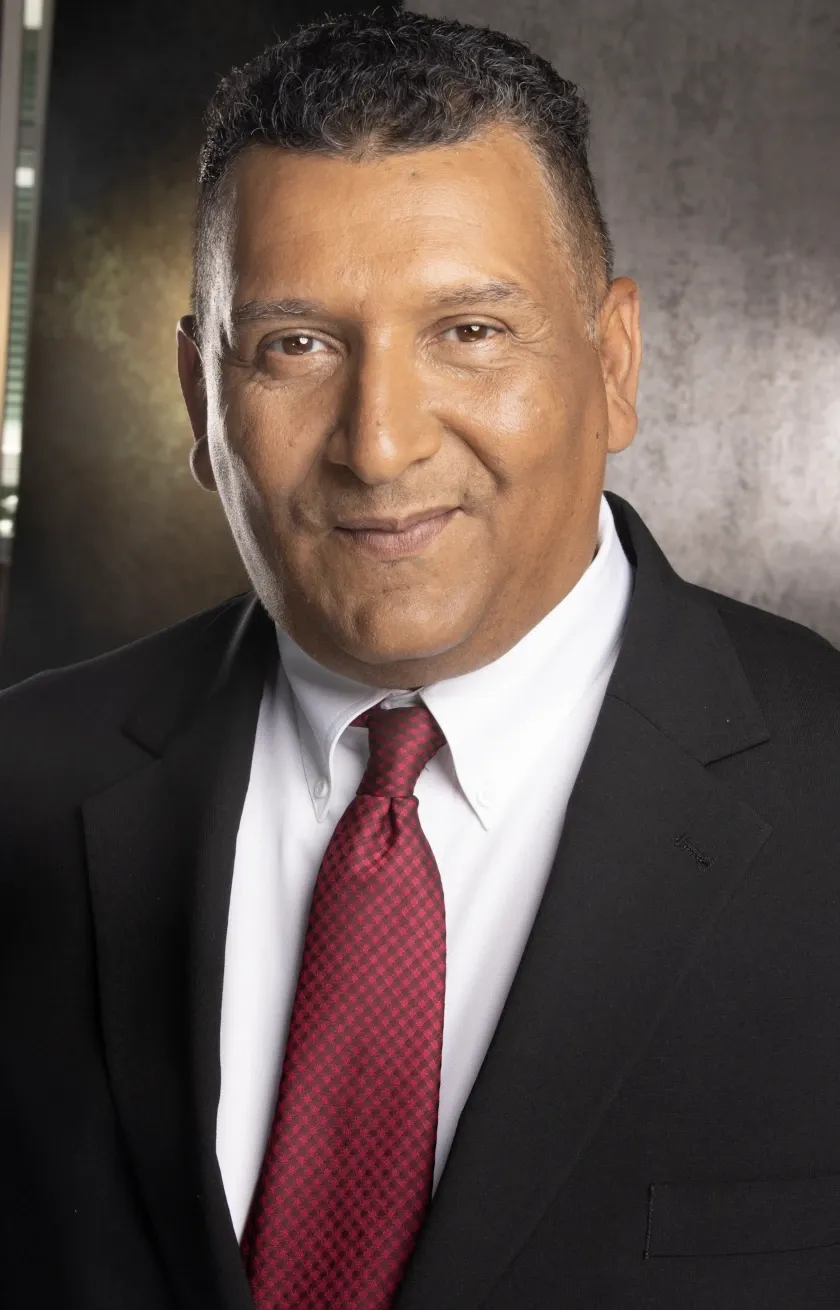

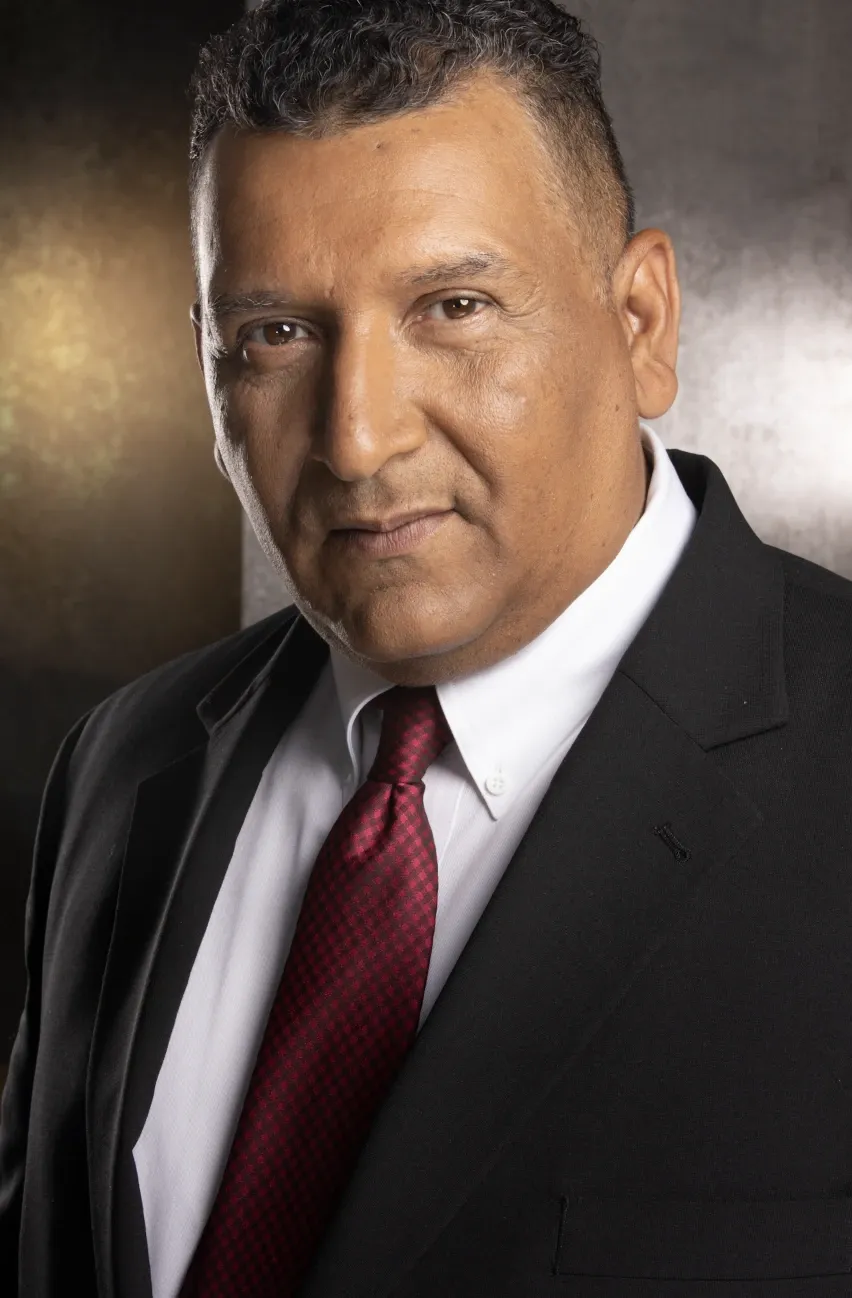

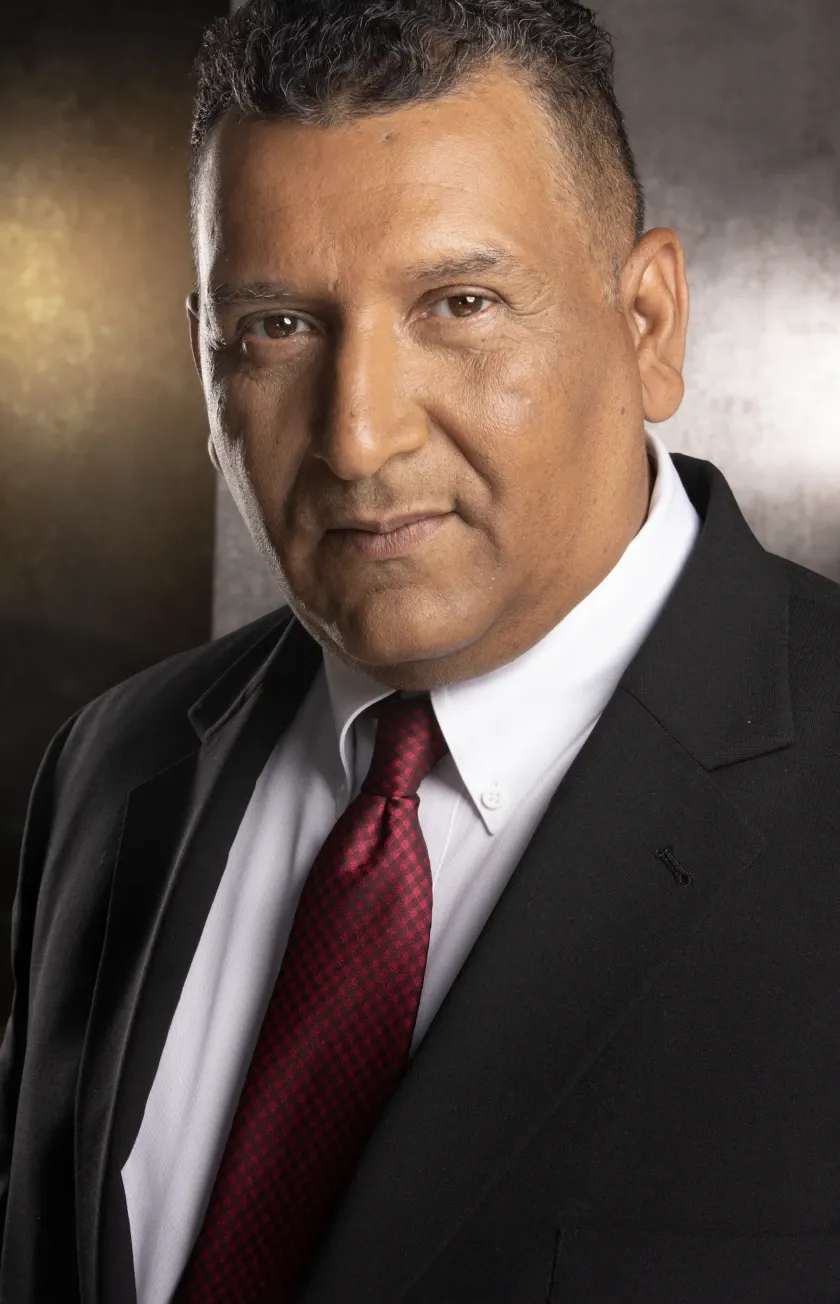

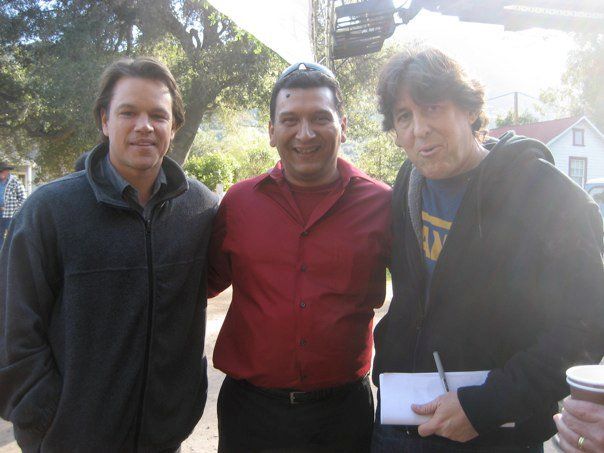

Roberto Montesinos

From Nuclear Reactor to Acting Stage: The At-Sea Chapter

My journey as an Engineering Laboratory Technician (ELT) in the US Navy's Nuclear Power Propulsion Program was anything but static. After two years of intensive training and a unique assignment as a Staff Instructor, my path took an extraordinary turn: I was assigned to the USS Arkansas (CGN-41), the last nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser built by the United States.

A Global Journey to My New Home

Getting to the "Ark" was an adventure in itself. It involved a series of flights across continents and oceans – from the Philippines to Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, landing on the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CVN-65) off the coast of Madagascar next to Africa, and finally, a helicopter transfer to the USS Arkansas. I was lowered to the flight deck, as new Tomahawk missile additions prevented a direct landing.

Stepping below decks, I was immediately welcomed by a group of nine former students from my prototype training facility. Their generosity in greeting me made a significant first impression – a testament to the camaraderie that would define my time at sea. Even as a qualified ELT Staff Instructor, I learned I'd need to re-qualify to stand watch in the ship's engine rooms. This process typically took up to nine months.

Accelerating to the Forefront of Readiness

Leveraging my prior instructor experience, I qualified to stand watch as an ELT on the Arkansas in just five weeks. This accelerated qualification put me in a unique position. In my final interview with the Chief Engineer, I boldly recommended he place me on one of the six watch teams preparing for the next yearly Pentagon reactor safety inspections. I had been on such a team twice before during my time as a Staff Instructor, with excellent results.

After a brief, intense exchange, the Chief Engineer signed my qualification card and informed my Division Officer and Chief that I was replacing someone on an inspection team. This was it – my training was about to hit a new level.

The Crucible of Daily Drills

Every day we were at sea, the Training Division put us through rigorous propulsion plant drills. These weren't just theoretical exercises; they were full-scale simulations designed to push us to our limits. We started with equipment malfunctions: failing pumps, electrical panel explosions, and radioactive leaks. Then, the scenarios escalated to missile and torpedo strikes, bringing with them simulated fires, steam leaks, flooding, and multiple equipment failures.

These daily drills became my favorite time at sea. We worked as an integrated team, rapidly responding to emergencies, memorizing and executing complex casualty procedures, and providing quick verbal reports while following orders to restore the engine room to safe operation. We even practiced medical evacuations, ensuring readiness for every contingency.

From Engine Room to Acting Class: Unexpected Parallels

Years later, sitting in acting class rehearsing directed and undirected scenes, I found an unexpected parallel. The process of breaking down a scene, understanding character motivations, and collaborating with fellow actors felt remarkably similar to our propulsion plant drills – though arguably less life-threatening!

The key difference, and the actor's challenge, was personalization. In the engine room, there was no room for individual interpretation; it was about the ship and the crew. In acting, it's all about bringing your unique self to the material. Yet, the discipline, the rapid recall of procedures, and the intense teamwork I learned in the Navy were invaluable assets.

The Perfect Scores and Unprecedented Advancement

During an upcoming Pentagon inspection, I predicted to the Chief Engineer that I would be chosen for observation during a crucial evolution: sampling and analyzing the reactor plant's water. As the last ELT to qualify and be assigned to a watch team, I knew I'd be under scrutiny. My prediction was accurate. I was observed by a Navy Captain and achieved a "perfect score" – no faults noted. Then, I had to repeat the process under the eye of the inspection team's Admiral, again earning a "perfect score."

The Chief Engineer called me to his office, baffled by my consistent "perfect" samples. I explained that I had the same result at S7G because they tended to inspect the newest operators. My secret? While most ELTs had a "reader" guide them through the lengthy, time-sensitive steps for radioactive accuracy, I had memorized every step, stating them to the reader for confirmation.

My unconventional approach surprised the Chief Engineer. He assigned me to begin the qualification process for Leading Engineering Laboratory Technician – a senior qualification usually achieved after 2-3 years aboard, if at all, but I was offered it after only seven months. This qualification required final interviews with several senior officers, including the Commanding Officer.

The Most Valuable Lesson: Crew Morale

My final interview for Leading ELT was with Captain Robert Twardy, the Commanding Officer of the USS Arkansas. This was the most challenging "checkout" of my eight years as a Navy Nuke, and it delivered the most valuable lesson I had acquired in my life up to that point.

Captain Twardy impressed upon me that nothing was more important on that billion-dollar warship than "crew morale" – the collective feeling and atmosphere of the ship's crew, regardless of rank. Before signing my qualification card, he asked if he could count on me to help with the ship's morale. "Absolutely, Captain," I replied.

I kept my word. I began by, and maintained, saying hello to everyone I saw on the ship. One day at sea, I counted saying hello over two hundred times before I stopped counting. This simple act fundamentally changed my attitude and the quality of my days. My final three years on the Arkansas were the best of my Naval career. I will always be grateful to Captain Twardy for this phenomenal lesson.

This awareness of the value of "crew morale" is something I carry with me to every film or television production set. A day at sea on a warship is tough; a day on a production set is tough. But by fostering a positive atmosphere, we can still do incredibly cool work and have fun doing it.

Link to a history of the USS Arkansas put together by a former shipmate EM2 Allen Kraft who I stood my first watch with: https://cgn41.com/history.htm